Tracking the Versions of Moby–Dick

Melville began Moby-Dick in 1850 as “a romance of adventure, founded upon certain wild legends in the Southern Sperm Whale Fisheries” (Letter to Richard Bentley, 27 June 1850). Eighteen months later, after relocating his family to a Berkshire farm, befriending Nathaniel Hawthorne (to whom the novel is dedicated), working his farm, and researching into whales and whaling, Melville had transformed his “romance” into an experiment in fiction that mixes drama and meditation; Homer, Shakespeare, and the Bible; as well as tragedy and comedy. When done, Melville told Hawthorne, “I have written a wicked book, and feel spotless as the lamb” (Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, 17? November 1851).

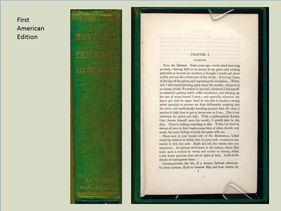

In the summer of 1851, and while he was still composing additional “chapters and essays,” Melville hired Manhattan printer Robert Craighead to typeset his novel and Harper & Brothers to market it in the US. Melville acted as his own copyeditor. To prevent the pirating of his text abroad, Melville followed the common practice of arranging for the near-simultaneous publication of his book in both the US and England. To do this, he sent corrected page proofs of the American version—what we now call Moby-Dick; or, The Whale—to his British publisher Richard Bentley, who reset the text, adding Melville’s changes and making hundreds of other changes, including scores of lengthy expurgations of sexual, political, and religious content. Melville’s manuscript and altered page proofs have not been located.

Bentley converted the American version into a more elegant three-volume set, titled The Whale; or, Moby Dick. In that process, he also repositioned “Etymology” and “Extracts” to the end of volume three and, famously, dropped Melville’s “Epilogue.” While this British edition was published in October 1851 and the unaltered American version one month later, the American edition is in fact Melville’s earlier version. These two print versions are the basis of Moby-Dick as a fluid text. In 2006 John Bryant and Haskell Springer offered their Longman fluid-text print edition of Moby-Dick, which uses a corrected and minimally emended version of the American first edition as a reading text to which they added contextual annotation, tables of textual variants, and revision narratives explaining the British alterations. For its Versions of Moby-Dick digital edition, MEL adopts the Longman print text as its Reading Text.

In the Works: Adaptation

Along with Typee, Moby-Dick has probably been Melville’s most illustrated work, especially in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. By one count in 1976, there are over 115 abridgments and written adaptations of Moby-Dick, in picture books for children, chapter books, and comics. The novel has been translated in over 22 languages, sometimes in abridgment as well. Fine artists, including Frank Stella, have created works, explicitly “about” Moby-Dick, that do not so much attempt to explain the novel as inhabit its aesthetics or ideas. Dramatic adaptations, especially in the decades since Orson Welles’s 1955 “Moby-Dick Rehearsed” have appeared on stage, TV, and radio. Film versions began with John Barrymore’s silent 1926 The Sea Beast and its 1930 sound remake. Ray Bradbury and John Huston’s 1956 film “Moby Dick” was the first of several powerful postwar cinematic adaptations. Musical compositions inspired by Melville’s novel include Jake Hegge and Gene Scheer’s memorable 2010 opera “Moby-Dick.” The popular imagination is rife with versions of Moby-Dick: Ahab’s mutilation, anger, obsession, and revenge have become a “meme,” recognizable by people who have never read or heard of Herman Melville.

While these forms of adaptive revision are “non-authorial,” in the sense that Melville never lived to supervise their creation, they nevertheless document how a culture chooses to perceive Melville’s work, in light of their own condition. In order to understand this phenomenon, we must have ways to link adaptive versions of Moby-Dick to the original Moby-Dick, which itself exists in two versions. As part of our efforts in editing Typee and “Benito Cereno,” MEL will be exploring protocols for linking reading texts to different kinds of adaptive revisions (sources and announced adaptations) that will enable us retroactively to enhance Versions of Moby-Dick in this direction as well. In addition, MEL has begun assembling materials regarding the 1956 Bradbury-Huston screenplay and film.

- VERSIONS OF MOBY-DICK: A Fluid-Text Edition

- Projects in the Works