Tracking the Versions

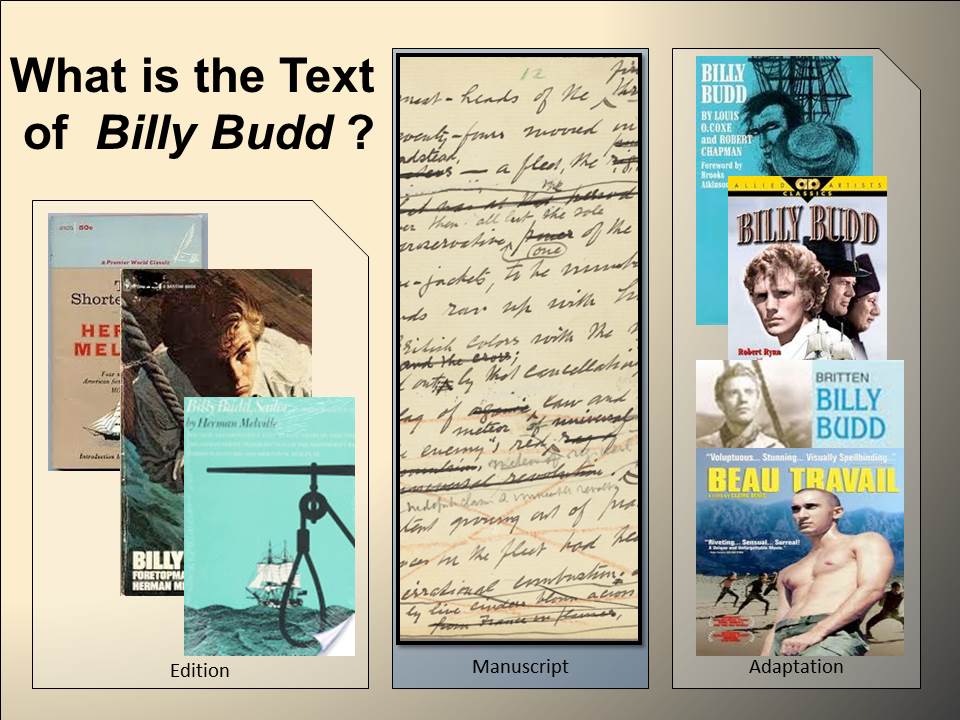

The surviving manuscript of Billy Budd is not a finished “fair copy” suitable for submission to a publisher for copy-editing, typesetting, and proofreading. Instead, it resembles a working draft riddled with revisions. Soon after its discovery among Melville’s papers in 1919, a transcription was published by Raymond Weaver (1924). F. Barron Freeman published his 1948 transcription based on a fuller analysis of the manuscript. Adding to his work and settling on a different transcription, Harrison Hayford and Merton M. Sealts, Jr. published a third version in their “genetic” edition of 1962. The 2017 Northwestern-Newberry edition of Billy Budd offers a modified, unmodernized version of the 1962 text. Melville’s text, then, exists in multiple versions, in manuscript and print, none of which Melville saw through the press or authorized.

How the Billy Budd manuscript grew is itself a fascinating story first sketched out (in part erroneously) in Freeman then more fully expanded in Hayford and Sealts. Melville first conceived of a ballad, now known as “Billy in the Darbies” (meaning “Billy in chains”). The poem is a dramatic monologue spoken by a beautiful, sexually mature mutineer, who is guilty as charged and about to be hanged. The ballad and the brief prose headnote that introduces it was originally intended to accompany similar but more nostalgic prose-and-poem monologues found in the 1888 John Marr and Other Sailors, but Melville put it aside. In three major phases of composition, Melville expanded the headnote, adding chapters-long sections more fully describing Billy, and then his nemesis, the mysteriously envious and iniquitous master-at-arms John Claggart, who falsely accuses Billy of mutiny, and whom Billy impulsively strikes dead. In a third phase, Melville added the fatherly but authoritarian Captain Edward Fairfax Vere, who manipulates a drumhead court to condemn Billy to death. In additional revision phases, Melville composed three concluding chapters that bring the reader back to the ballad, which Melville had also revised, making the formerly guilty sailor innocent. (Click here for storyboards visualizing How Billy Grew.)

This growth is discernible because in cutting and pasting chunks of manuscript text from earlier versions, as he added new material to expand his narrative, Melville also renumbered his leaves, in different colors, enabling scholars to deduce some eight stages and numerous sub-stages of composition, ranging throughout his three and more phases of development. Single leaves might consist of two or three slips of paper layered over and straight-pinned to each other, each leaf segment revealing further revisions, some in pencil, some in ink, or both, and a few in the hand of Melville’s wife, Elizabeth Shaw Melville. Unfortunately, in his cut-and-paste process, Melville discarded more text than he retained or revised, so that there are too many missing pieces to reconstruct out of the surviving patchwork manuscript any coherent narrative for each of the revision phases or stages.

Even so, a close inspection of the thousands of revisions sites, spread out over the manuscript’s 361 leaves, reveal startling insights into Melville’s evolving text. A couple of examples indicate the value of editing revision for critical analysis. One site on Leaf Image 17 shows how Melville’s revision of “white forecastle-magnate” to “handsome sailor” is part of his earlier insertion of an African sailor as an example of a character type that he was creating a name for: the “Handsome Sailor.” Though Billy is white, the inclusion of the African as equally beautiful required Melville to de-racialize his notion of masculine beauty. In effect, he was elevating Billy as a sailor who is white and handsome to Billy as an example of the non-racial Handsome Sailor Type.

In a related revision regarding race, Melville modifies his use of the pernicious stereotype “a son of Ham” in describing the African sailor. First he revises so that the African possesses “the best blood of Ham” and then revises to “the unadulterate [sic] blood of Ham.” While we might wince at the equation of “blood” and hereditary excellence, the effect of Melville’s revision is to dismantle the biblical curse of Ham and replace it with an authentic appreciation of black (in this case African) culture. Melville’s linked revisions, triggered by his insertion of an African into his narrative, also occurred in the late 1880s during the height of white supremacist lynching throughout the nation, including New Jersey not far from Melville’s home. Had Melville lived longer into this worsening era of lynching and especially given his tendency to revise incessantly, it is fair to ask whether and how Billy Budd might have continued to grow into other versions: either larger into a novel or smaller into a short story. The unstable manuscript that survives is essentially a fluid text frozen by Melville’s passing.

The Melville Revival of the 1920s, which retrieved Moby-Dick from relative obscurity, also brought Billy Budd before the public for the first time. By the late 1940s, it had captured the attention of critics and artists alike, and Melville’s novella continued to be revised in adaptation: Louis Coxe and Robert Chapman’s 1951 stage play, Benjamin Britten and E. M. Forster’s 1951 opera, and Peter Ustinov’s 1962 film. Claire Denis’s 1999 film Beau Travail—which recasts Melville’s British naval setting of the Napoleonic Wars to the modern French Foreign Legion of the colonial African desert—is remarkable evidence of Billy Budd’s enduring impact.

MEL’s Versions of Billy Budd gives readers unprecedented access to Melville’s revisions in manuscript. MEL will also extend the edition to include the adaptive revisions of Billy Budd evident in play, opera, and film. But navigating from our Billy Budd Reading Text to adaptations that add, subtract, or revise episodes, scenes, speeches, and images across genres and media requires new strategies and technologies. Our plan, then, is to develop our approach to adaptive revision in our editing of Melville’s first publication Typee, which is Melville’s fullest fluid text, that encompasses variant versions in manuscript, print, and adaptation. For more on editing adaptation, click here.

-

VERSIONS OF BILLY BUDD: A Fluid-Text Edition

- How to Use the Edition

- Enter the Edition

- Tracking the Versions: Billy Budd

- How Billy Grew

- Modes of Digital Editing

- Collations

- Billy Budd: Manuscript Base Version v. MEL Reading Text

- Billy Budd: 20th-century Reading Texts

- Project Ideas