Modes of Digital Editing

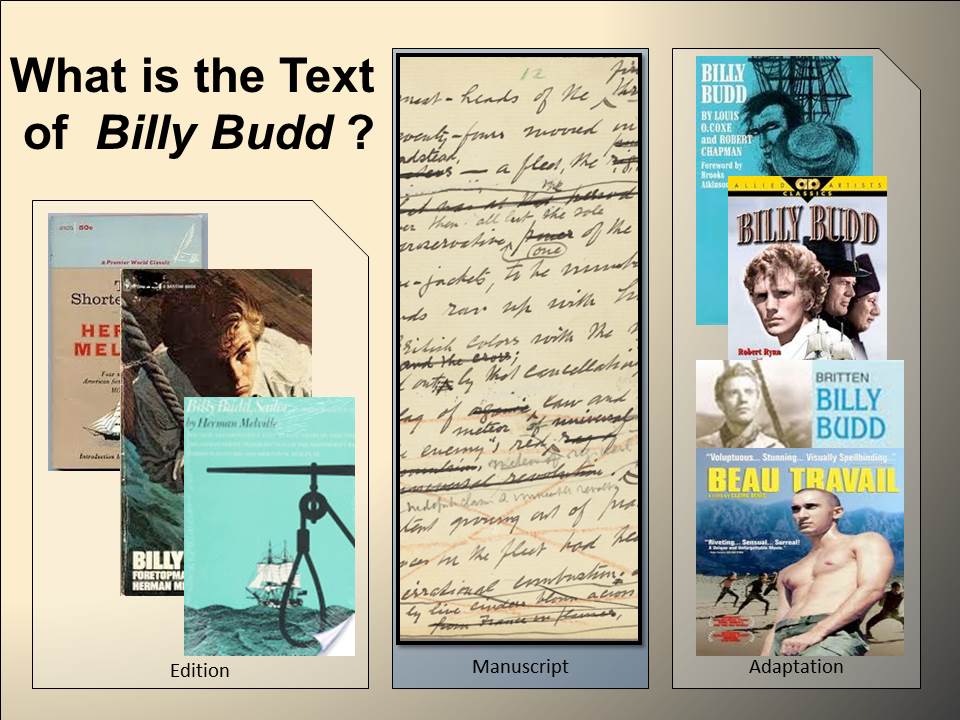

Two problems in accessing the versions of a fluid text are 1) how to maximize the reader’s contact with each physical version (manuscript, print, adaptation as objects) without losing the reader in the network of versions, and 2) how to facilitate readers in comparing the texts of versions so they can make knowledgeable critical interpretations in the form of revision narrative. The first problem is easily addressed by placing physical versions side-by-side. (See, for instance, MEL’s side-by-side display of the American and British first editions of Moby-Dick.) However, the kind of analysis derived from the comparison of the texts of versions is best achieved by using a Reading Text as the textual terrain upon which links to versions and revision annotations are added, as we do with the marginal thumbnail leaf images that take readers deeper into the Billy Budd manuscript itself.

Generally speaking, in selecting a version for an edition’s reading text, we choose the physical version that is large enough to accommodate links to variants in other versions. To create the reading text for Billy Budd, we lightly edited the manuscript’s base version, correcting (and recording) all non-substantive errors, dropped and doubled words, and incomplete punctuation. Both Base Version and Reading Text are the product of three successive modes of editing, designated in MEL as Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary. In each mode, editors proofread the text against MEL’s digital images of the manuscript itself.

General Editorial Principles.

In editing Billy Budd in revision, the editor’s initial obligation is to transcribe the manuscript, which includes describing the physical object itself as well as original, revision, and marginal texts. The editor is also obliged to facilitate readers in unpacking the revisions, making Melville’s additions and deletions visible and explaining possible revision sequences. In keeping with the protocols of fluid-text editing laid out in Bryant’s The Fluid Text, MEL performs these two editorial functions in separate stages. In Primary Editing, we transcribe the manuscript texts, including the identification and coding of revision sites, as text objects only. In Secondary Editing, we use this marked-up primary transcription code to create revision annotations, which delineate revision sequences and explain them in revision narratives. While TEI codes exist for integrating secondary revision sequencing within primary transcription, MEL’s “stand-off” approach—a standard in digital humanities scholarship—separates these two editorial modes, for two reasons.

- Revision sequencing (secondary editing), especially in cases involving multiple revision sites, is unavoidably speculative so that a single set of revision sites might yield multiple sequences or multiple narratives for a single sequence, depending upon the editor’s interpretation of the revision act. If revision sequence codes were integrated into the primary transcription coding, the transcriber’s single revision sequence and narrative—an interpretive process and a matter of debate—would be codified as part of the primary transcription, risking the likelihood that the transcriber’s coding of the revision sites—additions, deletions, restorations, etc.—as text objects might be inflected to support the individual transcriber’s subjective interpretation of the revision itself.

- While TEI permits sequence codes as part of revision mark-up, an editor seeking to add an alternative sequence would have to do so by altering the original transcription code, a cumbersome task that would likely discourage the development of alternative revision scenarios.

Better, then, to keep description and interpretation as separate editorial acts. By separating the primary and secondary editing functions, we seek to create manuscript transcription data that is as “objective” or as “granularized” as possible so that future editors can draw upon the same data to fashion separate and variant revision sequences and narratives. MEL’s stand-off approach is easier for editors, scholars, and students to manage, and it enables us to store all narratives of multi-stepped sequences and narratives for comparison in side-by-side display, thereby generating a discourse field for the discussion of Melville’s revision process.

Primary Editing.

We use TextLab to mark-up Revisions Sites on the digital image of each manuscript leaf and to transcribe the leaf’s entire inscription (including its revision texts).

In marking-up revision sites, the editor draws boxes (or zones) around each distinct unit of revision. TextLab automatically assigns a unique number to each box. The box numbers are arbitrary and do not represent revision sequencing; they merely identify the zone so that the text inside, when transcribed, can be associated with the zone. As noted above, no attempt is made in primary mark-up to encode revision sequencing. That more interpretive editorial function is performed separately in secondary editing. But, to ensure flexibility in the sequencing process, and to avoid inadvertently ruling out sequence options, our mark-up strategy is to seek a high degree of granularity, erring on the side of more rather than fewer boxes. For instance, in a single revision act, Melville might delete one word, insert a caret, and add another word above the deletion. This familiar enough revision scenario would receive three boxes, one for each revision element: the deletion, addition, and caret. The transcriber might box the three as one, and code them using the interpretive TEI code <subst>, which bundles an <add> and <del> together to suggest that the writer has “substituted” the one for the other. However, to do so automatically imposes a subjective sequencing into the descriptive transcription. The reason we opt for three boxes instead of one is that it enables secondary editors more flexibility in determining the relation of these three revision units, whether it is the immediate substitution they appear to be, or a series changes that involve other, intervening or associated revision acts.

Another scenario also argues for granularity in primary editing. Three words appearing to be deleted in one stroke might be marked-up in one box as a single revision site. But a closer inspection aided by digital magnification might reveal that what appears to be a single stroke is actually achieved through two overlapping deletion strokes: one for one word; another for the other two. By drawing two boxes instead of one, editors can, in secondary editing, more fully explain a two-step, rather than one-step, revision process. Primary editors also use TextLab to code the specific attributes of a revision text—where it is placed, whether in ink or pencil, etc.—inside each box. MEL’s attribute codes and coding strategies are discussed in Transcription Coding.

Secondary Editing.

If primary editing transcribes the Billy Budd manuscript as a physical text object, the goal in secondary editing is to describe revision sequencing through annotation. In this process, the editor selects a set of revision sites that have already been marked-up, transcribed, and coded in primary editing and composes a Revision Sequence and Narrative that explains Melville’s revision process, step by step, at those sites.

A workspace in TextLab for composing revision sequences and narratives facilitates this revision annotation process. The workspace is a table with columns for step number, revision site number, revision step, and revision narrative for that step. When the editor selects a revision site, that site’s box number is entered as a step in the “site” column. In the adjacent “step” column, the editor copies the revision text for that site and enough inscription surrounding it to provide meaningful grammatical context for the passage being revised. In the “narrative” column, the editor describes the how, why, and impact of this single revision step. Additional sites are entered for additional steps until the full sequence and narrative are completed.

TextLab automatically stores each revision sequence / narrative in the edition’s database. Editors can submit multiple sequence / narratives for the same revision sites, and readers can view and compare all sequence / narratives that have been formally accepted into the edition. In MEL’s Projects section, instructors will be able to create accounts for classroom assignments.

Tertiary Editing.

This third mode of editing encompasses the making of the Reading Text and both textual and contextual annotation.

Because the “base version” of the manuscript is neither complete nor in all places coherent, it must be edited into readable form and format. The first goal in tertiary editing is to bring the Reading Text into existence. At this stage, previous editors of Billy Budd have taken the liberty to regularize, standardize, and modernize Melville’s spellings and punctuation, correct errors of historical fact, and “smooth” over internal inconsistencies and other “rough” spots in the text due to incomplete revisions. On the one hand, such editorial smoothing is designed to enhance the reading experience for today’s reader, but it does so at the risk of obscuring the reality that Billy Budd, in its base text version, is fundamentally unfinished and a rough read. On the other hand, leaving the unpolished Billy Budd base version unedited would confuse and alienate readers. In transforming base version to reading text, editors of Billy Budd typically work to achieve the most serviceable balance between rough and smooth that reflects their editorial goals.

As discussed in more detail in Emending the Reading Text, MEL emends the Billy Budd base version lightly, by making corrections that will facilitate a smooth enough reading experience but also by retaining enough rough moments in the text to remind readers that Billy Budd is a significantly unpolished and in some cases incomplete work. MEL used Juxta Editions—a digital platform for scholarly editing—to perform this task. The base version text of the Billy Budd manuscript was imported from TextLab into MEL’s Juxta Editions workspace, where editors then further emended the text and format it for conventional reading.

In keeping with scholarly editing protocols, MEL’s editors record all changes of wording and punctuation in correcting the base version. Most of these textual notes are perfunctory and are recorded without explanation; they include the supplying of obvious dropped words or words doubled up due to an imperfect insertion or deletion; or the adding of neglected punctuation such as quotation marks for dialogue and grammatically necessary (not stylistic) commas. Most of Melville’s persistent misspellings, such as “beleive” or “unfortunatly,” would have been corrected by professional copy-editor, if Melville had submitted Billy Budd for publication, and since they are likely to annoy readers, or be perceived as typos, we correct them as well. This protocol includes changing Melville’s idiosyncratic “do’nt” to the conventional “don’t,” though the 2017 NN version of Billy Budd retains “do’nt,” citing precedence during Melville’s life for that usage. For MEL, preserving this roughness risks peculiarizing Melville’s text, so we have smoothed it over, with a textual note recording the change.

Certain textual moments involving an apparent incoherency or incomplete revision naturally provoke editorial decisions on whether or not to emend the text and therefore necessitate fuller annotation. Two such rough spots left intact in MEL’s Billy Budd reading text are worth mentioning. The more controversial is our treatment of the name of the British man-of-war onto which Billy has been pressed. Beginning in Chapter 1 and running throughout most of the manuscript, the war ship is called Indomitable (for a total of 22 times); however, in Chapters 18 and 28 the ship is called Bellipotent (6 times). Previous editions have opted to regularize the name: Weaver changed the six Bellipotents to Indomitable, and Hayford and Sealts did the opposite, changing all 22 Indomitables to Bellipotent. The 2017 NN Billy Budd follows suit. MEL, however, retains each instance of both names where they occur in the manuscript. The fact that in no instance did Melville actually delete an Indomitable in order to insert a Bellipotent suggests a distinctive (perhaps tentative) category of revision: Did Melville intend to change all names to Bellipotent but did not live to complete the changes; or was he simply experimenting with a new name and neglected to make up his mind? This degree of uncertainty warrants MEL’s decision to retain both names, and we supply a textual note at the first appearance of each name explaining our decision not to regularize to one name or the other. An added value of this decision is that it alerts readers to the incomplete condition of Billy Budd.

A second intended editorial roughness involves Melville’s misspelled word “lustrius” used in Chapter 1 to describe the African sailor’s complexion. The intended word is either “lustrous” (meaning shiny) or the less conventional “lustrious” (meaning glowing, radiant, splendid). The 1962 Hayford and Sealts edition adopts “lustrous,” and the 2017 NN edition “lustrious.” MEL, however, retains the misspelling, with a textual note explaining both word options, leaving it to readers to consider the different connotations of each option, as it relates to the African’s surface or inner beauty. MEL’s decisions to keep the different kinds of textual roughness evident in the variable ship name and the misspelled lustrius give some sense of the balance of rough and smooth reading we intend to convey in our Billy Budd reading text.

MEL will also use the reading text for linking to contextual notes that explain historical, political, cultural, and aesthetic references; MEL will use FairCopy (the upgraded iteration of Juxta Editions), also designed by Performant Software, to perform these tasks. FairCopy will allow readers to filter textual, contextual, and revision narratives on and off in various combinations for different reading experience of the Billy Budd Reading Text. With FairCopy we will also collate (i.e. compare) MEL’s base version and reading text with the major 20th and 21st-century transcriptions of Billy Budd (Weaver, Freeman, Hayford and Sealts, and NN). By highlighting differences between these versions, MEL will be able to document evolutions in the editing of Billy Budd as a fluid text, from manuscript into its modern print versions.

- VERSIONS OF BILLY BUDD: A Fluid-Text Edition

- Modes of Digital Editing

- Collations

- Billy Budd: Manuscript Base Version v. MEL Reading Text

- Billy Budd: 20th-century Reading Texts

- Project Ideas