How to Use the Edition: Moby–Dick

MEL’s scholarly edition of Moby-Dick, titled Versions of Moby-Dick, was edited and formatted in MEL’s instance of the Juxta Editions platform, adapted by and managed through Performant Software Solutions, and updated to FairCopy. The following Introduction describes our goals for the edited text, our editorial process, and directions on how to navigate the edition. To enter the edition, use the link to the right. To return to this or other MEL pages, click the MEL tab on your browser.

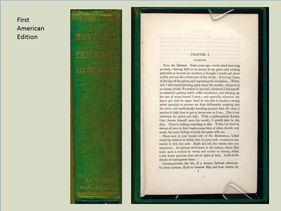

When you enter Versions of Moby-Dick, you will find a Table of Contents to the left, listing each chapter of Moby-Dick. Click on a chapter to bring that chapter’s Reading Text into the center column. Down the right margin are thumbnail images of each page in the American edition for the selected chapter. Mousing over a thumbnail will highlight the corresponding text for that page.

Reading Text.

The central feature of MEL’s Versions of Moby-Dick edition is a digital version of a reading text prepared by John Bryant for his and Haskell Springer’s 2006 Longman Critical Edition of Moby-Dick. Bryant used a Word copy of a transcription of the first American edition prepared at the University of Virginia’s Text Center and proofed his transcription against digital images of the American edition pages and against the 1988 Northwestern-Newberry (NN) edition of Moby-Dick. Bryant also double-checked the NN list of variants from the British first edition and the Harper’s New Monthly Magazine version of “The Town-Ho’s Story” as well as the NN editors’ list of emendations to their American copy-text. In the Longman textual apparatus, Bryant published a list of variants including the American, British, and NN editions, and made point by point decisions on whether to emend the American copy-text. He provided textual notes on selected variants and NN emendations and on all Longman emendations.

MEL’s fluid-text editorial approach differs from the NN approach in several ways. The NN edition seeks to render a reading text of Moby-Dick that represents the editors’ conception of the author’s final intentions. It selects a copy-text that comes close to that state of intentionality, in this case the first American edition text, collates (compares) it against the British edition text, and inspects all variants for evidence of authorial intentions that, if adopted, would, in theory, bring the copy-text even closer to representing the author’s final intentions. Where emendable problems arise in the reading text that cannot be resolved by adopting a British variant, the NN editors also create new wording of their own to address the problem. Many of these textual decisions are discussed in the NN Textual Apparatus. Because the NN critical edition’s reading text mixes versions, it is considered an “eclectic edition.”

In constructing its fluid-text editions, MEL adopts a more restrained approach to emendation. Rather than mixing versions, it seeks to render a reasonably coherent, readable version, or reading text, of the American first edition “as it exists” rather than as a representation of an editorial conception of what the writer might have intended. Our goal for this reading text is to create a textual terrain on which we can map subsequent authorial, editorial, and adaptive versions of Moby-Dick. In this way, textual changes (including Melville’s revisions and editorial expurgations evident in the British edition) can be displayed and analyzed separately, thus preserving the separate textual identities of both American and British editions. This is not to say, that MEL does not emend the American copy-text. In pursuit of a reasonably coherent reading experience, MEL corrects obvious typos, such as “kifferent” for “different,” but does not attempt to modernize the text, resolve authorial errors (such as misidentifications of characters), or correct inconsistencies, unless not doing so would significantly confuse readers. Instead of fixing these problems by emending copy-text, MEL offers textual notes explaining the textual problem.

Bryant’s lists of textual variants, emendations, and problems in the Longman edition are being added as textual notes to the Reading Text in Versions of Moby-Dick. Variants in the British edition that represent possible authorial revisions or British changes in mechanics or expurgations are treated as revision narratives in the Longman edition and will be transferred to MEL’s collation display of the American and British versions once the transition to FairCopy is made. For further discussion, go to Collating Moby-Dick. Selected revision narratives are also included as revision annotations in the Reading Text.

Textual and Contextual Annotation.

Currently, MEL’s reading text displays layers of contextual annotation drawn from notes prepared by Haskell Springer and Bryant for their Longman critical edition and from notes prepared by MEL’s Art, History, and Travel Groups. Apart from the revision annotations also included, these notes fall into several distinct categories of annotation.

- Textual: Brief notes register British variants and MEL and NN emendations.

- Glosses: MEL adopts from the Longman edition an array of notes that briefly define arcane words or usages and nautical terms.

- Contextual: Longer explanatory notes offer discussions of Melville’s sources and his historical, political, and cultural references. These notes drawn from the Longman edition are also now augmented by links to images and data on Artworks, Person, and Event in MELCat.

- Art: MEL’s Arts Group has also used MELCat to develop a database of Melville-related Artworks in various media, linked to relevant notes, via Juxta Editions’s note feature.

- Geographical Imagination: MEL’s Travel Group has created a database of places (real, mythic, or imagined, visited or not visited by Melville) mentioned in Moby-Dick.

All these layers of annotation will be attached to MEL’s reading text of Moby-Dick and eventually made filterable so that readers can turn all, some, or none on and off.

Side-by-side American and British Versions.

An added feature of Versions of Moby-Dick is MEL’s side-by-side display of the 1851 American first edition of Moby-Dick and the 1851 British first edition of The Whale.

Projects.

MEL anticipates future development of our Projects space where readers interested in Melville scholarship will find tools (like TextLab and Itinerary) and workspaces (like our proposed Melville ReMix) that will enable them to create essays, exhibits, maps, or presentations based on content in MEL’s Archive and Editions sections. One project already in the works is a study comparing Ray Bradbury’s screenplay of John Huston’s 1956 film “Moby Dick to Melville’s original text.

- VERSIONS OF MOBY-DICK: A Fluid-Text Edition

- Projects in the Works